history of christianity timeline pdf

The history of Christianity spans over 2,000 years, beginning with the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. It traces the faith’s origins, key events, and global spread, shaping Western civilization and beyond.

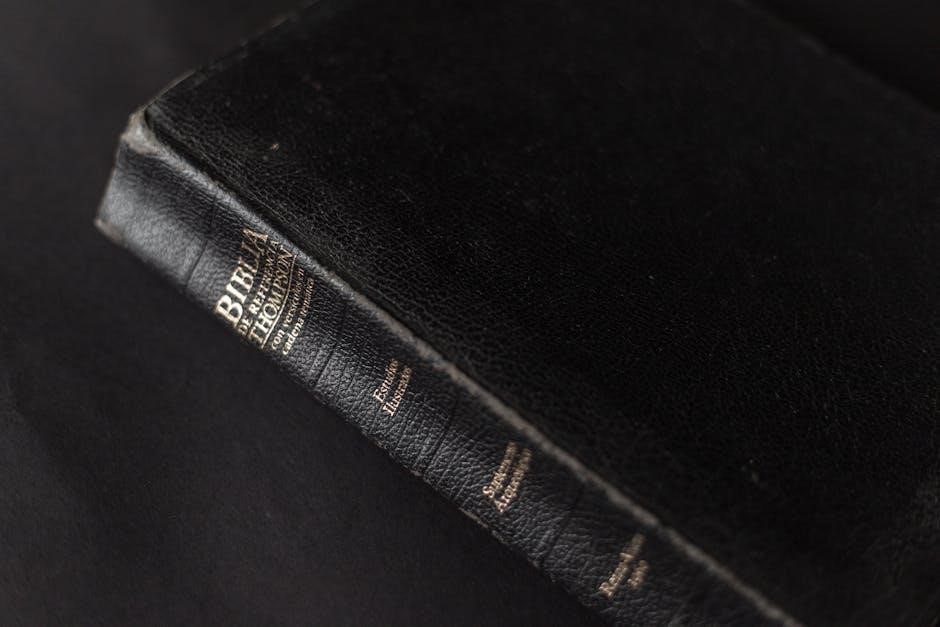

1.1. The Biblical Foundations of Christianity

The biblical foundations of Christianity are rooted in the Old Testament, which recounts the creation of the world, humanity’s relationship with God, and the covenant with Abraham. Key figures like Moses, the prophets, and King David shaped Israel’s history and spiritual identity. The New Testament builds on this, narrating the life, teachings, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, seen as the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecies. These scriptures form the theological and historical basis of Christian faith, emphasizing themes of redemption, love, and salvation.

1.2. The Life and Ministry of Jesus Christ

Jesus Christ, born circa 4 BC, is the central figure of Christianity. His ministry began around 30 AD, emphasizing love, forgiveness, and the Kingdom of God. He performed miracles, preached parables, and gathered disciples, including Peter, John, and Matthew. The Last Supper, where he instituted the Eucharist, marked the end of his ministry. His crucifixion and resurrection are core to Christian belief, symbolizing redemption and eternal life. These events are detailed in the Gospels, forming the heart of Christian theology and practice.

1.3. The Formation of the Early Christian Church

The early Christian Church emerged after Jesus’ resurrection, with His apostles as leaders. The Great Commission and the Day of Pentecost marked its beginnings. The first followers, predominantly Jewish Christians, established communities in Jerusalem. The Church structured itself with leaders like Peter and James, addressing theological and organizational challenges. The Jerusalem Council (circa 50 AD) resolved conflicts over Gentile inclusion, fostering unity. This period laid the foundation for Christianity’s spread through missionary journeys and the writings of the New Testament, shaping the faith’s identity and mission.

The Early Christian Church (1st–5th centuries)

The early Christian Church grew rapidly, spreading across the Roman Empire despite periodic persecutions. Key events included the Edict of Milan (313 AD) and the Council of Nicaea (325 AD), which established foundational doctrines and unified the faith, shaping its institutional structure and theological identity.

2.1. The Apostolic Period and the Spread of Christianity

The Apostolic Period, spanning the 1st century AD, marked the foundational spread of Christianity. Following Jesus’ resurrection, His disciples, led by Peter and Paul, preached to Jews and Gentiles alike. The conversion of Cornelius, a Roman centurion, signified the faith’s expansion beyond Jerusalem. The Antioch church emerged, where followers were first called “Christians.” Missionary journeys by Paul and others established early churches across the Mediterranean, laying the groundwork for Christianity’s global reach.

2.2. Persecution of Early Christians in the Roman Empire

Early Christians faced severe persecution in the Roman Empire, often blamed for societal unrest. Emperor Nero notoriously scapegoated Christians for the Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD, leading to brutal executions. Martyrs like Saints Peter and Paul became symbols of faith. Despite this, Christianity persisted, with believers enduring suffering while spreading their teachings. The persecution highlighted the tension between Roman authority and the growing Christian movement, shaping its resilience and identity in the early centuries.

2.3. The Edict of Milan and the legalization of Christianity

The Edict of Milan, issued by Emperor Constantine in 313 AD, marked a pivotal moment in Christian history by legalizing Christianity within the Roman Empire. This decree ended centuries of persecution, allowing Christians to practice their faith freely. It also restored confiscated church properties and granted religious tolerance to all citizens. The Edict symbolized the Empire’s shift toward Christianity, paving the way for its rise as a dominant religion. This period of peace enabled the church to flourish and lay the groundwork for future theological developments.

Christianity in the Roman Empire (4th–5th centuries)

Christianity became the state religion under Emperor Theodosius, influencing Roman politics and culture. The Empire’s division and eventual fall in the West marked a significant turning point for the faith.

3.1. The Council of Nicaea and the Establishment of Doctrine

In 325 AD, Emperor Constantine convened the Council of Nicaea to resolve theological disputes, particularly Arianism, which denied Jesus’ divinity. The council affirmed the Trinity, establishing the Nicene Creed as the cornerstone of Christian doctrine. This gathering marked the first ecumenical council, uniting bishops from across the empire to define orthodoxy and ensure theological unity. The Council of Nicaea laid the foundation for Christian doctrine, clarifying the relationship between God the Father and Jesus Christ, and its decisions remain central to Christian theology today.

3.2. The Rise of Monasticism and the Desert Fathers

Monasticism emerged in the 3rd–4th centuries as a response to persecution and societal corruption. Desert Fathers like Anthony of Egypt pioneered asceticism, seeking spiritual purity through solitude, prayer, and self-denial. Monasteries became centers of learning, preserving Christian texts and fostering communal life. This movement emphasized humility, work, and devotion, shaping Christian spirituality and influencing the broader Church. The Desert Fathers’ teachings on prayer and moral discipline remain foundational to Christian practice, bridging the early Church with the medieval period.

3.3. The Fall of the Western Roman Empire and Its Impact

The Western Roman Empire’s fall in 476 CE marked a pivotal moment for Christianity. Without imperial patronage, the Church lost a key secular power that had supported its growth since Constantine. However, this void allowed the Church to consolidate its influence, particularly in Western Europe. Bishops and monasteries became central to societal stability, preserving learning and order amidst chaos. The Eastern Roman Empire continued to support Christianity, ensuring its survival and adaptation in a changing world. This period laid the groundwork for the Church’s medieval dominance.

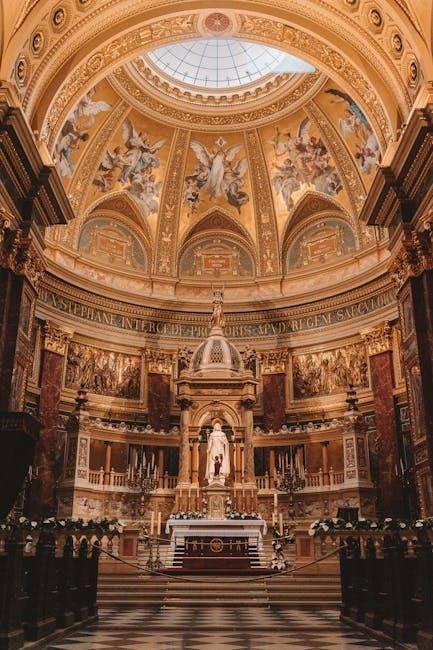

Christianity in the Middle Ages (5th–15th centuries)

During the Middle Ages, Christianity became deeply intertwined with European culture and politics. The Catholic Church rose to prominence, shaping society through theology, art, and governance.

4.1. The Rise of the Papacy and the Catholic Church

The Middle Ages saw the papacy emerge as a central authority in Christianity. The Catholic Church solidified its influence through doctrine, hierarchical structures, and the leadership of key popes. This period also marked the rise of monasticism and the development of theological frameworks that shaped Christian practices and beliefs, further establishing the Church’s role in both spiritual and temporal affairs across Europe.

4.2. The Crusades and Their Influence on Christian History

The Crusades, initiated by Pope Urban II in 1095, were a series of military campaigns aimed at reclaiming the Holy Land from Muslim rule. These wars profoundly shaped Christian history by fostering religious zeal, strengthening papal authority, and altering relations with Islam and Judaism. While they achieved limited territorial gains, the Crusades had lasting effects on religious tolerance, cultural exchange, and the political landscape of Europe and the Middle East, leaving a complex legacy in Christian history.

4.3. The Scholastic Movement and Theological Developments

The Scholastic Movement, flourishing in the 12th to 14th centuries, sought to integrate faith and reason through Aristotelian philosophy. Key figures like Thomas Aquinas synthesized theology with classical thought in works like Summa Theologica. This period emphasized dialectics, debate, and systematic theology, shaping Christian doctrine. The rise of universities like Paris and Oxford fostered intellectual inquiry, making scholasticism a cornerstone of medieval Christian thought and education, profoundly influencing both theology and Western philosophy for centuries.

The Reformation and Counter-Reformation (16th century)

The Reformation, sparked by Martin Luther’s 95 Theses in 1517, challenged Catholic Church practices, leading to Protestantism. The Counter-Reformation, marked by the Council of Trent (1545–1563), sought reform within the Church, reaffirming doctrine and revitalizing Catholic identity, shaping a divided Christian landscape.

5.1. Martin Luther and the Protestant Reformation

Martin Luther, a German theologian, sparked the Protestant Reformation by publishing his 95 Theses in 1517, criticizing Church practices like indulgences. His emphasis on salvation through faith alone challenged Catholic doctrine, leading to a theological and ecclesiastical rupture. Luther’s ideas, supported by the printing press, spread rapidly, inspiring reform movements across Europe. His translation of the Bible into German made scripture accessible to laypeople, fostering a personal connection with faith. This movement laid the groundwork for diverse Protestant denominations and reshaped Christianity globally.

5.2. The Council of Trent and Catholic Renewal

In response to the Protestant Reformation, the Catholic Church convened the Council of Trent from 1545 to 1563. This ecumenical council reaffirmed Catholic doctrine, addressing issues like justification, sacraments, and Church authority. Trent promoted liturgical reforms, emphasized clerical education, and revitalized monastic life. It also led to the formation of the Jesuits, who played a key role in Catholic renewal. The council established a counter-reformation strategy, ensuring the survival of Catholicism and shaping its identity for centuries to come.

5.3. The Emergence of Major Protestant Denominations

Following the Reformation, various Protestant denominations emerged, shaped by distinct theological perspectives. Lutheranism, rooted in Martin Luther’s teachings, emphasized justification by faith. Calvinism, influenced by John Calvin, focused on predestination and strict moral codes. Anglicanism arose in England, blending Catholic traditions with Protestant reforms. Anabaptists and Baptists emphasized adult baptism and church-state separation. These denominations diversified Christianity, fostering theological debates and cultural transformations across Europe and beyond, while maintaining core Protestant principles like sola scriptura and individual faith. This period marked the permanent fragmentation of Western Christianity.

Christianity in the Modern Era (17th–20th centuries)

Christianity faced challenges from the Enlightenment, which promoted rationalism and secularism, while missionary work expanded its global reach, and events like Vatican II brought modernization to the Church.

6.1. The Enlightenment and Its Impact on Christianity

The Enlightenment emphasized reason and science, challenging traditional religious authority. Thinkers like Locke and Voltaire advocated for tolerance and criticized church power, influencing Christian theology. Deism emerged, questioning supernatural elements, while some Christians adapted, emphasizing personal faith and morality. The period saw a shift from institutional to individual spirituality, shaping modern religious thought and practices.

6.2. Missionary Work and the Global Spread of Christianity

Christian missionary work flourished during the 19th century, driven by European colonization and religious zeal. Organizations like the London Missionary Society and the Church Missionary Society sent missionaries worldwide. Christianity spread rapidly in Africa, Asia, and the Pacific, adapting to local cultures while promoting Western values. Missionaries established schools, hospitals, and churches, leaving a lasting legacy. This period marked Christianity’s transformation into a global religion, shaping societies and fostering cultural exchange, despite challenges like resistance and ethical concerns surrounding colonialism.

6.3. The Second Vatican Council and Modernization

The Second Vatican Council (1962–1965), initiated by Pope John XXIII, aimed to modernize the Catholic Church. It introduced sweeping reforms, including the use of vernacular languages in liturgy, increased lay participation, and greater openness to other religions. The council emphasized ecumenism and interfaith dialogue, fostering unity among Christian denominations and engaging with global challenges. Vatican II marked a pivotal shift toward a more inclusive and adaptive Church, influencing modern Catholic identity and its role in the contemporary world.

Contemporary Christianity (20th–21st centuries)

Contemporary Christianity encompasses ecumenical efforts, the rise of Evangelicalism, and addressing global issues. The Church adapts to modern challenges, seeking unity and relevance in a diverse world.

7.1. Ecumenical Movements and Interfaith Dialogue

Ecumenical movements aim to unify Christian denominations, while interfaith dialogue fosters understanding with other religions. The 20th century saw the founding of the World Council of Churches (1948) and Catholic participation in ecumenism through Vatican II (1962–1965). Landmarks include the lifting of mutual anathemas between Catholics and Orthodox (1965) and the 1996 Joint Declaration on Justification. These efforts reflect Christianity’s commitment to unity and global religious cooperation in the modern era.

7.2. The Rise of Evangelicalism and Pentecostalism

Evanglicalism emerged in the 18th century, emphasizing personal conversion, biblical authority, and missionary outreach. The 20th century saw its global expansion, particularly in the Global South. Pentecostalism, beginning in the early 1900s, focused on the Holy Spirit’s gifts, such as speaking in tongues. The Azusa Street Revival (1906) was a key catalyst. Both movements have grown rapidly, reshaping modern Christianity, with Pentecostalism becoming one of the fastest-growing religious movements worldwide, especially in Latin America, Africa, and Asia.

7.3. Challenges and Opportunities in the 21st Century

Christianity faces challenges like secularism, declining attendance in the West, and religious persecution globally. However, rapid growth in Africa, Asia, and Latin America presents opportunities for renewal. The rise of technology and social media enables global outreach, while interfaith dialogue and ecumenism foster unity. Addressing issues like poverty, inequality, and climate change aligns with Christian values, offering a platform for transformative engagement. These dynamics shape Christianity’s role in a changing world, balancing tradition with modern relevance.